One thing that intrigues me is why a significant number of serious bicycle collectors and bespoke builders of the boutique, modern steel frame are based in the United States. May be they are more vocal than everyone else. My question is: How can a country that took to cycling as an adult sport more than half a century after the safety bicycle made cycling popular everywhere else, hijack and claim expertise in an area of transport they did little to create?

One obvious reason why I hold this belief is because of my limited language skills and patent inability to follow anything not written in plain English (If you speak Italian, French, or Japanese and have something to say beyond “pasta”, “baguette”, or “sushi” then I’ll smile, nod politely, and go back to sipping my beer). So exposure limited to the English-language (not to mention an Anglo-Saxon, Christian-monotheistic framework) is partly to blame. But even using Google searches from other countries (google.it, google.fr, google.co.jp etc) brings a lot of American portals to the front page.

So I got the troll to look into it. (in English)

An interesting graph comes courtesy of the Earth Policy Institute via Global Sherpa (www.globalsherpa.org/world-bike-market-eco-indicator-international-development).

One would assume that, given the enormous price and technological differences, the global sale (per unit) of bicycles would always massively outnumber the sale of cars (accepting that one’s perspective is that of an average joe with a peculiar fondness for bicycles). This does not appear to be the case. According to this graph the per unit sale of bicycles hovered just above the unit sale of cars until the late 1960s. From Global Sherpa: “The timing of the sharp increase and divergence in bike and car production aligns well with a particularly productive time in the world’s economic development. Over the period 1970-2009, the average increase in the Human Development Index (HDI), which correlates closely with per capita income levels, for countries around the world was a healthy 44 percent.”

I take that to mean that from the 1970s some of those that would otherwise have gone on foot managed to get more coin and started to use a bicycle to, from, and for work. And they may have even splashed out on a bicycle for their kid/s.

Indeed, at the start of the seventies, some of those that drove an automobile started to take to riding a bicycle.

And so we turn our attention to the United States.

And so we turn our attention to the United States.

The US bicycle boom in the early 1970s was a major shakeup for the bicycle industry. This graph (via wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bike_boom) shows bicycle sales in the United States exceeding motor vehicle sales for the first time (albeit just briefly) from 1972-1974.

More specific details of US bicycle sales via Ken Kifer’s Bike Pages (http://www.kenkifer.com/bikepages/lifestyle/70s.htm) are as follows:

1960 3.7M bicycles sold

1965 5.6M

1970 6.9M

1971 8.9M

1972 13.9M

1973 15.2M

1974 14.1M

1975 7.3M

1971-1974 clearly shows a pretty impressive surge followed by an equally dramatic slump in bicycle sales in the United States. And the start of the bicycle boom in the US preceded the 1973 oil crisis (the OAPEC oil embargo started with the Yom Kippur War and lasted from Oct 73 - Mar 74). So the crisis was not the cause of America’s explosive interest in bicycles but it may have played a role in prolonging it an extra year (Frank Berto, The Dancing Chain) or even contributed to its sudden crash when oil prices stabilised.

These two graphs taken from http://mysite.verizon.net/vzerndgo/id76.html show graphically the extent of the overall bicycle boom in the US and the breakdown between “lightweights” (ie 10-speed adult geared bicycles) and other bicycle models (predominantly children’s bikes).

So a bicycle boom definitely happened in the United States in the early 70‘s - that much is certain. But to try and comprehend how this all came about we may have go back in time to a decade earlier...

...to the 1963 Schwinn Sting-Ray.

According to Re-Cycle (http://www.re-cycle.com/History/Schwinn/Swn6_Sting-Ray.aspx) and John Brain (http://bikerodnkustom5.homestead.com/brainhistory63_muscle2.html) in the early 1960s kids on the West Coast of the United States started putting "Texas longhorn handlebars" on to old bicycles in an attempt to emulate the style of a chopper motorcycle. Schwinn management soon learnt about this and the Schwinn Sting-Ray was subsequently introduced in May of 1963. By the end of the year they had sold just over 45,000 units. This was a phenomenal number at a time when the most popular production bicycle models sold at ~10,000 units/yr. An achievement made even more extraordinary given the mid-year release (but well timed for the American summer), radical appearance, and initial skepticism from the bicycle trade.

The interest in children’s “apehanger” bicycles started off as an American fad but did spread worldwide (at least in the English-speaking world). The UK, more conservative than the Separatists they had sent off on the Mayflower, took over 5 years to warm to the idea. And boy was that a warm reception when it happened. The Raleigh Chopper was released in the UK in September 1969 (timed perfectly with the renegade motorcycle movie “Easy Rider”), sold 1.5 million units in the UK and Europe over the ensuing 10 years (Frank Berto, The Dancing Chain), and has become one of the iconic symbols of growing up in the 1970s. A great deal more information about the Raleigh Chopper and its development is available at http://homepage.ntlworld.com/catfoodrob/choppers/history/index.html.

Back in the United States the market for children’s bicycles had become saturated by the start of the 1970’s. Although the ongoing sales of (now expensive) bicycles for children continued to buoy the total number of bicycles sold in the US, the growth during the boom years was for adult “racing” or “touring” derailleur-equipped bicycles (ie "lightweights" in the graph above).

Throughout the 60s the United States already had a reasonably popular, domestically produced, geared bicycle in the form of the Schwinn Varsity (as well as the slightly upmarket Schwinn Continental). Introduced in 1960 the Varsity weighed in at over 40lb, targeted the inexperienced, young teenage market, and was well-received (unlike the adult-orientated Continental model which was met by a poor reception when introduced in the mid 1950s). By most accounts the Varsity was a popular model but did little to spark the imagination of the average American - apart from introducing the concept of the derailleur-equipped bicycle. To cater for the rare top-end bicycle enthusiast, Schwinn (the dominant player in the US market) continued to provide their limited-production Paramount model equipped with Campagnolo equipment if only to assuage the trickle of racing bicycles making their way across the pond. (Schwinn did produce intermediate-range, fillet-brazed bicycles but unfortunately managed to debase them in the 60s & 70s so they became largely indistinguishable from lower-end Varsity and Continental models http://www.sheldonbrown.com/schwinn-braze.html)

1960 Schwinn Varsity. Note the Simplex Tour de France rear derailleur and Competition lever-operated front derailleur (via http://www.schwinncruisers.com/schwinn-documentation/1960-schwinn-bicycle-models/)

1960 Schwinn Continental

By the mid 60s the Varsity had 10 speeds and Huret Allvit derailleurs (via http://www.creativepro.com/article/scanning-around-with-gene-getting-that-new-bike-down-the-chimney)

So why then did a country in love with technology and addicted to fully-mechanised fossil-fueled methods of transport, hitherto paying scant regard to the human-powered-albeit-mechanically-assisted two-wheeled pedal-pushing variety, suddenly develop an interest in the bicycle? More importantly, what did this mean to the bicycle industry as a whole?

In part, the Schwinn Sting-Ray (and the Varsity to a lesser degree) increased the average American’s familiarity with the bicycle as it became a common household item by the late 60’s - early 70’s (along with innovations like Tupperware, a refrigerator with a separate freezer compartment, and colour television). Humans, much like other life forms with more than one reproductive cycle, are most comfortable amongst things that they are familiar with. And, as always, timing is of the essence. An important demographic was starting to make its mark over this period. The age group responsible for much of the innovation and many of the ill’s that make up the modern world: the baby boomers...

United States birth rate (births per 1000 population). The blue segment is the postwar baby boom. (via Wikipedia)

The generation that grew up in the affluence of a postwar world wanted a change from traditional values. They experimented with recreational drugs, sexual liberation and rock and roll (ably assisted by various concoctions of the Devil notably the transistor radio, the birth control pill, and, of course, the quietly conspicuous and permissively psychedelic lava lamp). Individualism (or unrepentant hedonism depending on your point of view) and the counterculture movement peaked in the period from the end of the sixties to the start of the seventies and arguably reached its zenith in the United States with the publication of “The Greening of America” in 1970.

By the start of the 1970’s the children that grew up with the apehanger (and the occasional derailleur) bicycle had matured into a heaving mass of politically and culturally influential teenagers and young adults. And they were looking for something else beyond sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Something to bolster their mortal bodies for the legacy they would leave the rest of the world (a reality forced to the forefront of public awareness as cardiovascular diseases at their peak in the 1960s accounted for 55% of annual deaths in the United States).

And so the 1970’s was also the start of the American fitness craze.

Not only was there an interest in exercise but posing in sports clothes started to become fashionable. Matching bottoms were added to the sports tops-cum-anoraks worn by athletes and the tracksuit was born.

To look cool in a tracksuit in the 70s you had to be Bruce Lee

To look cool in a tracksuit in 2003 you had to be Uma Thurman wearing a tailor-made piece

(Quentin Tarantino referencing Bruce Lee from his unfinished final movie = subzero supercool)

Back to the topic. Television revolutionised the broadcasting of sports in the 1960s and business was set to exploit this market in the 1970s. Sports entertainment became an industry of its own with spectator sports like football, baseball, basketball, boxing, auto racing, golf, and tennis becoming big business. Over this decade professional athletes fought for and won the right to “free agency” (autonomy to market themselves to the highest bidder rather than being traded by their teams) and were given advertising opportunities in areas that had nothing to do with their sport. This was the decade that sports megastars suddenly became mega-rich.

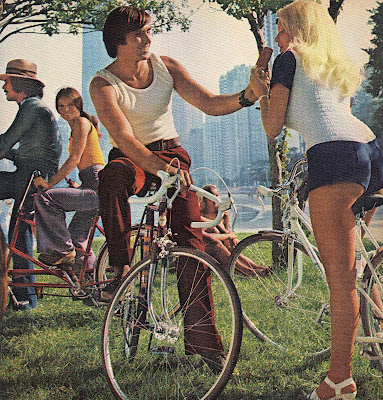

It was in this setting that the activity of bicycling made it’s impression as a worthwhile adult activity in the United States. It is important to recognise that the bicycle boom occurred at the start of the American fitness craze and appears to have gained momentum, along with the recognition of other noncompetitive health activities (such as yoga, aerobics, isometrics, stretching etc), caught up in the wave of enthusiasm. It is equally important to recognise that this period (1971-1974) predates the wearing of bicycle-specific clothing amongst the non-racing set (at least in the United States) and also predates the movie “Breaking Away” (released in 1979). Vast amounts of money was yet to revolutionise the profile of the professional athlete (and in any case vast amounts of money didn’t hit professional cycling until decades later). But the impetus for these things happening evolved over this time.

So maybe the US bicycle boom was a result of individualism and the counterculture movement (as a reaction to materialism and other traditional attitudes on race, sex, authority etc that youth in a relatively affluent society had the leisure to revolt against - not to mention that this tumultuous period oversaw the birth of the politicised environmental movement), or the burgeoning interest in sports at the start of America’s fitness craze (bicycling being one of many sports that gained recognition), or the maturation of the “ten-speed” bicycle (oh goodness, two gears up front and 5 at the back, and I’ll take an imported butted steel frame thank you very much), or a passing health fad of the large and influential generation of baby-boomers (who had grown up on chopper-style bicycles and now had jobs and money to burn). May be it was a combination of all these factors. The end result was from 1972 to 1974 American demand for the geared adult bicycle skyrocketed. And supply chains simply couldn’t keep up.

In 1970 just 12% (820,000) of the 6.9 million bicycle sold were derailleur-equipped adult lightweight bicycles (Frank Berto, The Dancing Chain). By 1972 nearly 14 million bicycles were sold with 7-8 million (depending on your source of information) being lightweights. By the peak of the boom in 1973 over 15 million bicycles were sold with 70% being lightweights. In the rush to meet demand (and make a handsome profit in the process) US bicycle manufacturers and importers pumped out large numbers of bicycles at the expense of quality control and sales acumen. The vast majority of “lightweights” were low cost, gas-pipe (heavy-gauge unbutted tubing) frames with cheap alpine (wide-range) gears. It was over this period that the Japanese, having already established a toehold in the American market in the early 60s, set themselves a reputation of producing relatively inexpensive, good quality bicycles and components. Having maintained strict quality control on the frames and equipment they produced for their domestic market they continued that standard when exporting overseas. And they managed to maintain focus combining value with astute marketing when meeting the specific demands of the noncompetitive but discerning US consumer. It might have been difficult for a hardened bicycle enthusiast to admit that an $8 slant-parallelogram Suntour RD shifted better than a $40 Campagnolo RD (Frank Berto again) or that a Japanese-built Bridgestone or National (Panasonic) “Schwinn-Approved World bicycle” with Shimano gearing could outperform an American-built (and more expensive) Chicago Varsity or say a French-built Peugeot. But a naive cycling population unfamiliar with cycling’s historical pretensions called the game as they saw it.

And this was the time for reassessing the state of play of the derailleur itself. European derailleur stalwarts Campagnolo, Huret and Simplex saw the wind shift towards Japanese upstarts, Shimano and Suntour over this period. Sure, this was the American leisure market and not top-end professional racing but it was the start of a new era. The following decade saw the demise of Huret and Simplex and the challenge of Campagnolo’s dominance at the top of cycling’s world order.

The 1973 Schwinn World Voyager made by Panasonic using butted Tange tubing and fitted with Shimano Crane GS rear and Titlist front derailleurs, Dura-Ace crankset, Suntour barcon shifters and DiaCompe centre-pull brakes, mounts a serious challenge to Schwinn’s home-made Paramount model with Campagnolo groupset... and at half the the price... (via http://detroit.craigslist.org/okl/bik/2401982926.html)

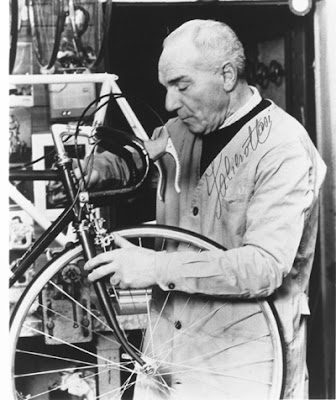

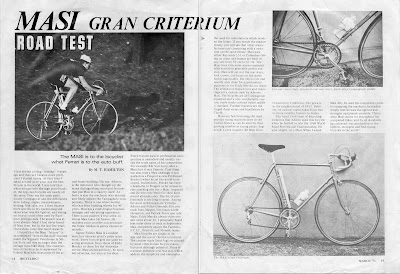

That’s not to say that top-end bicycles did not make it across the pond from England, France and Italy (as well as Japan). One could still get a Cinelli Supercorsa or, with greater persistence and patience, an Alfred Singer or a Rene Herse, or a Hetchins or a Condor built by none other than Bill Hurlow himself. But it was only ever a tiny fraction of the bicycle market and the booming sales in the United States did little to increase their presence. Nonetheless a Southern California businessman by name of Roland Sahm saw an opportunity to market top end, European-inspired but American-made, racing bicycles during the boom. Roland apparently contacted a number of internationally respected builders with his business proposition but they all turned him down with the notable exception of one Faliero Masi. Faliero consulted with his long-time American associate, Ted Kirkbride, and in 1972 or 73 (surprisingly no agreement for such a significant date) Faliero Masi moved to Carlsbad, California (http://www.harobikes.com.tw/harobikes/masi/2008/history.html). He took with him a talented frame builder by name of Mario Confente and through his Californian workshop passed what would become the roots of American custom framebuilding: Brian Baylis, Jim Cunningham, Albert Eisentraut, Dave Moulton, Joe Stark, Mike Howard and David Tesch (http://www.ebykr.com/2005/12/masi/).

Faliero Masi “The Tailor”

1971 article on Faliero Masi in Bicycling! magazine

At the end of the American bicycle boom the United States overtook Europe as the principle market for quality racing bicycles (Frank Berto, The Dancing Chain). The Japanese had established themselves as a reliable, value-orientated bicycle and component manufacturer. A nascent group of top-end framebuilders had established a reputation for themselves in the United States. And the Americans, with their typical enthusiasm and brash disregard for tradition, then went on to give the world the BMX bicycle and the mountain bike.

And, to come up to date, let’s not forget that the United States also bestowed the world of professional road racing (the blue-ribbon, public face of bicycling) a chap by name of Lance Armstrong. Love him or loathe him (cyclists seem to hold very polarised opinions on the swaggering Texan - no room for casual indifference here), and leaving aside allegations of drug use and bullying, he has made bicycling a recognised global sport. More specifically as the most recognised cyclist alive (again leaving aside comparisons with the other giants of our sport), he has pulled cycling into the front pages of the English-speaking general public.

Controversial but nonetheless inspirational

Outside of cycling, the United States remains as the world’s only military superpower, still has the world’s largest economy and contains the 3rd largest population after China and India. Indeed, it appears that 2/3 of the readers of this blogsite are American (and I thank the both of you).

Goes to show that, big or small, relevant or nugatory to the way we go about our daily lives, and whether we like it or not, what happens in the United States matters.

Goes to show that, big or small, relevant or nugatory to the way we go about our daily lives, and whether we like it or not, what happens in the United States matters.

(for a more cohesive and validated account of the American Bicycling Boom and other arcane details about the development of the derailleur bicycle, I highly recommend Frank Berto’s excellent book “The Dancing Chain”)

1 comment:

Enjoyed reading post on your blog.!

Post a Comment